For the past eight months, I’ve been working on a body of paintings that I hope to share soon. However, I stepped away from writing in this space (Substack) for the last four months as I’ve been trying to come to an understanding of how to articulate what my artwork is, my process, and my insights. It has been a slow process. Some aspects have been intentionally slow; much like my paintings, life is layered and nuanced, and it takes time to take shape. Some aspects are slow by nature because of my own confusion about how to articulate my work and the experiences that are being imbued in it. I don’t know. I’ve gone back to the drawing board, scrapped what I’ve written and pressed delete one too many times. In doing so, I’ve given myself the space and permission to delve down the rabbit hole of researching my influences—the mentors I would have dreamed of approaching for advice, asking them about their own experiences and what they asked themselves when they were in this predicament.

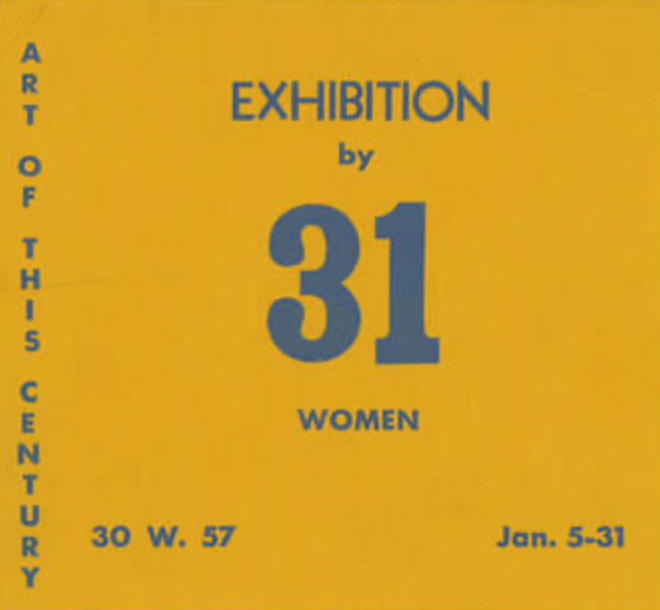

This has led to many more questions. My research, of course, started with the obvious—the women of the Abstract Expressionism movement, from Grace Hartigan to Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell to Lee Krasner, and the others, widely known as the 9th Street Women. But what I began to wonder more and more was why, when we speak of the women of the Abstract Expressionism Movement, does the conversation end with them? Why don’t we speak of the many other women artists who were relevant to those times and influential to the movement, albeit perhaps not widely known, even at that time?

It is easy to start with the most well-known female artists of that time, but as I continued, I found myself drawn from the obvious to the oblique. And that leads us to a question—where do we begin?

In a 1993 interview with Ruth Fine, when speaking about the Great Masters, Helen Frankenthaler noted,

“… I’ve often said this, to me it is very beautiful to see a show, and there are many cases here where just in the permanent collections you can see the spawning of one artist pushing and developing and working with others, and the sense of, I am in many ways a traditionalist and believe heritage and also believe in the unknown, and the improbable happening maybe, but that there is a continuity in everything, whether it is poetry, painting, philosophy, or music and a real development, and everything else around it becomes worthy and noticeable and maybe forever there, but eventually assumes its place as a satellite. And an offshoot is placed…”

Interview with Helen Frankenthaler

When I listened to this interview and heard Helen Frankenthaler speak, I couldn't help but wonder: Who was pushing whom during that time? Who were the artists that aren’t widely known? What environments were fostering and creating the foundations from which “those seeds were starting to bloom”? Who were the art collectors and curators pushing their work forward in the greater cultural dialogues about what art is, its worthiness, and its legacy-making? Who were their “siblings,” and what did they take from their influence?

In my pursuit to uncover, understand, and answer these broad questions, I’m struck by a deep curiosity about the ephemeral qualities of these artists and their work. What idiosyncrasies and obsessions did they bring to their creations? What factors helped shape not only the work itself but also their voice and internal understanding of why and how they approached their practice?

As I began this journey of uncovering and piecing things together, I realized that, although time is linear, we exist in concentric circles. The wider constellation of life and all that has come before is worthy of discovery and curiosity, and there is a strong likelihood that we are all but degrees of difference—yet still somehow connected. But where do we begin?

In 1978, the artist Nancy Graves was asked by Mimi Posner in an interview about her work and how it relates, insofar as it is gestural painting, with Abstract Expressionism as practiced by Pollock or Kline. Graves said,

“When I was a student, which was in the early '60s, my mentors were the Abstract Expressionists, and that was one of the things I would have given my right arm, which is the arm I use, to be able to emulate. However, what I recognized at the same time, through the foresight of my teachers and the fact of attempting to do this, is that one cannot attempt to imitate what is the dominant mode of working. That is to say, second- and third-generation De Koonings were not exactly as powerful because there was a mentor. So, as a professional artist, I attempted to ignore, so to speak, Abstract Expressionism.

I think a fact of history is time, and it’s now at least 20 years since De Kooning made those marvelous paintings, and almost 30 years since Pollock. Because of that, many other things have gone on. So what I’ve attempted to do at this point, was, because of that great admiration and my background, to allude to certain aspects of Abstract Expressionism but at the same time bring in as many or more references to my own work, and to create a structure that had to do with layering—different layering, different attitudes that I have utilized and brought forth stylistically, which are in the work—and to combine those in a way where an abstract painting was the result.”

In this way, I’ve begun to also ask the question of how we speak of our work with the seriousness that they brought to theirs. How do we speak about our work without having to explain our own womanhood? How do we speak of the act of creation without having to explain our relationship to motherhood? Can we speak of our artistic pursuits without having to bring our sex into the dialogue? Is it necessary? How far have we come since Linda Nochlin wrote the essay "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" in 1971? The work of the wonderful Katy Hessel, who wrote The Story of Art Without Men, only highlights how much still has to be done for women to be considered worthy of being included in the canon of art history, but how do we move forward with the same freedom that men have always had in allowing the Art speak for itself?

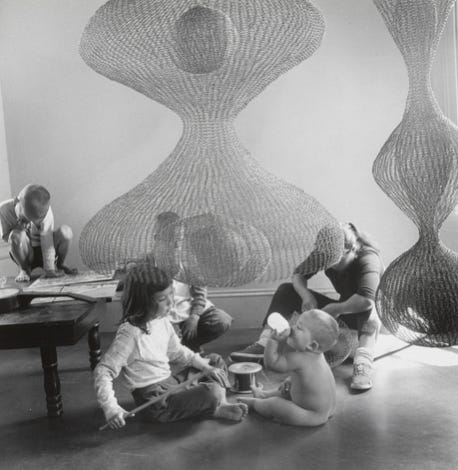

In an interview with Ruth Asawa’s daughter, Addie Lanier, and Meg Partridge, the granddaughter of Ruth Asawa’s longtime collaborator, the photographer Imogen Cunningham, at the Getty Museum, they were asked to speak to both artists' philosophies of being in a family and using the material they had, just working where they were. Addie noted that Ruth Asawa wrote,

“Imogen always felt that it was terrible for mothers to put a guilt trip on their children... if you say that you wanted to be an artist but you had to give it up because of your children. So what my mother and Imogen figured out how to do was work in mediums that allowed them to continually develop their eye, their expression, etc., their subject matter, and be fully a fulfilled artist and be mothers...”

Unfailingly Creative: The Unbreakable Bond between Artists Imogen Cunningham and Ruth Asawa

As an artist and writer, I feel it’s imperative—and that it is serious work—to explore the landscape of artists who came before us, those who were overlooked and underappreciated, and to understand what they were made of. How did they come to see the world and their work, and how were they shaped as artists?

I have come across many people in the creative field who have resisted the work of delving into the lives and works of the artists that came before them, fearing that there will be some cross-contamination—that it will somehow impede their ability to be authentic or original. While I can understand that to a degree, I strongly disagree and, in fact, find it disingenuous. If one truly believes in the notion of Art as an intangible essence that we are constantly struggling to grasp and express in a way that is true and honest, then it begs the question: do we not do ourselves a disservice by not understanding and being aware of, and honouring what has come before us? The wonderful Italian film director Luca Guadagnino speaks to the authenticity and originality of creativity in such a beautiful way in a conversation with the Belgian painter Michaël Borremans on the David Zwirner Podcast Dialogues. When asked about making work, he says,

“I think originality and newness is an obscenity, and what really counts is the point of view. And what really counts is the way in which a subject, or an object, can be seen through the perspective of a subjectivity. I always like to think of when 1001 Nights [was] written, that all the stories had been told, and all the images would kind of [have] been told...”

Dialogues: Luca Guadagnino and Michaël Borremans

I also understand more than ever, in this age of technology and oversharing, in the era of performance and likability, that there is a genuine desire to protect the mystery. To honor the silent ways we engage with the sublime nature of Art-making. But this has only deepened my desire to honor those who have stood before me. My ability to truly grasp where my work is coming from and what lies within me is bound by my need to dive deeper—uncovering more and more of the inner lives of the artists and their works. To do, as the brilliant French Film Director Agnes Varda so eloquently put it:

"If we opened people up, we’d find landscape; if we opened me up, we’d find beaches."

To be continued….